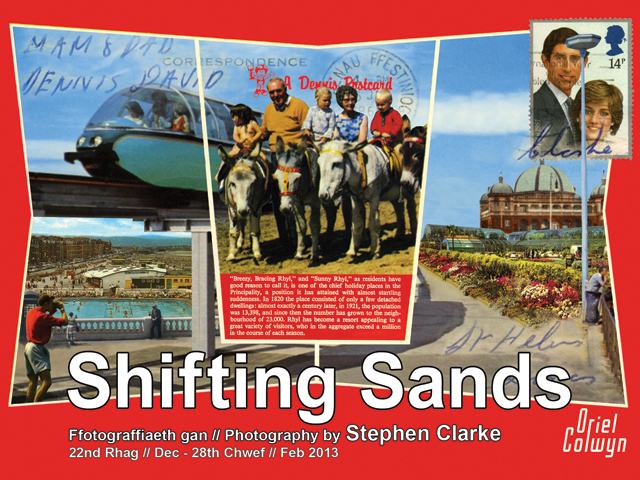

Shifting Sands – Stephen Clarke

December 22nd 2012 - March 15th 2013

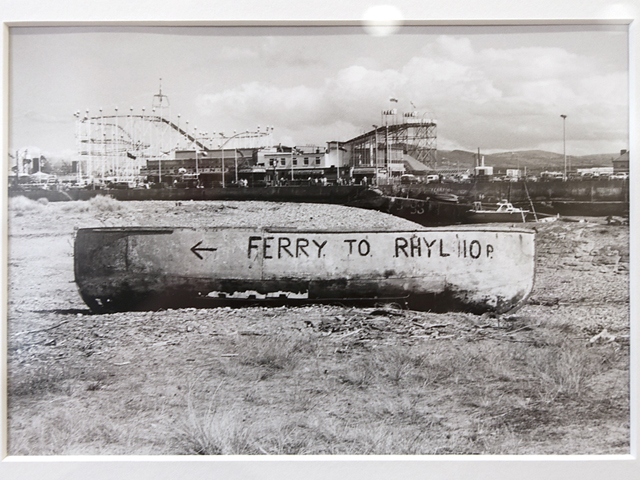

The fortunes of Rhyl seem to rise and fall like the waves on its beach. A once vibrant place is now, like many Victorian seaside resorts, either in decline or in transition. Stephen Clarke’s photographs and photomontages picture these changes. Melancholic black and white photographs depict sites now gone such as the ‘Ocean Beach’ funfair and the ‘Coliseum’ theatre, whilst the digital colour photomontages overlap text and images from celebratory postcards of different time periods in the resort’s history.

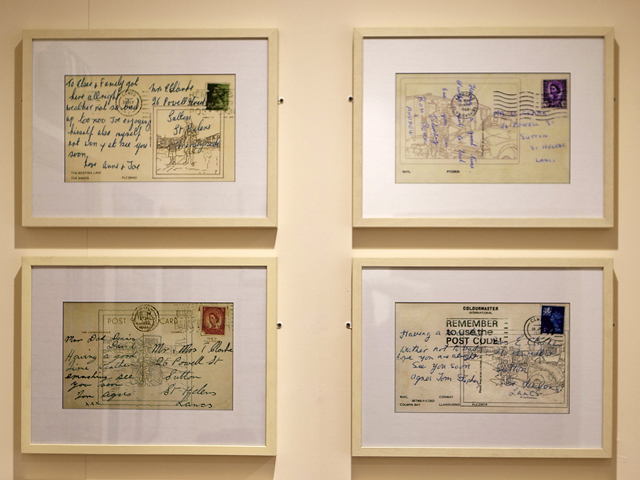

Stephen Clarke’s collection, centred on family snapshots, cine films and postcards, has informed his documenting of the town. This exhibition provides a topography of not just the town but also the family that visited the resort.

Review by Dr Emma Roberts

‘Shifting Sands. Photography by Stephen Clarke’, Oriel Colwyn, Colwyn Bay. December 22nd 2012 - 15th March 2013

Situated within the oldest theatre in Wales- Theatr Colwyn in Colwyn Bay- is, paradoxically, one of the newest galleries- Oriel Colwyn. This venue shows photographic work and is exhibiting currently ‘Shifting Sands. Photography by Stephen Clarke.’

Clarke’s subject matter is the nearby seaside resort of Rhyl: the once thriving tourist destination of Victorian holiday-makers. Over several decades, and with different media, Clarke has documented the town’s shifting fortunes and ephemeral landmarks and this exhibition integrates his various projects so that viewers experience an interpretation of the resort that is complex and long- considered. Rhyl is usually berated. However Clarke shows the town compassion, respect and directs the viewer seductively to recognise and then embrace the significance that the destination has for its residents and tourists.

Using vintage postcards from his family archive, Clarke created the larger and colourful works in the exhibition - photomontages that abound with exuberance, nuance and poignancy. Beneath these, and acting as quiet counterpoints, are his smaller black and white photographs that observe keenly. Across one corner of the room a screen relays snatches of conversation that provides additional texture to the experience of viewing the art work, and increase the sense that the viewer is required to penetrate multiple layers of information and meaning for the full significance to become clear.

Indeed, only on a superficial viewing does this exhibition have a simple theme. With more considered examination of the works the richness of their multiple meanings is revealed. Like the shifting sands of Rhyl, and in the exhibition’s title, gradually meanings materialise and change with repeated viewings. For example, although each photomontage or photograph exists as a discrete and complex image, study and repeated viewings uncover new themes and humorous signs. After some moments, it becomes clear that the order of the large photomontages is entirely specific and can lead the viewer on a nostalgic journey if they are receptive. Within each image is an object that one also finds repeated somewhere within the one that follows. The process is repeated with each work: one object is presented that will link to the next and another within the image also references the preceding work. In one instance, the pink elephant of a Rhyl amusement park ride can be spotted in smaller dimensions within the next photomontage.

Whilst seeking the clues that thereby form a narrative, one is led to become aware of the unconventional beauty within the scenes depicted. One photomontage depicts a street lined with 1960s cars of colours so vivid that they seem to contemporary eyes to be airbrushed but- no- these Neopolitan ice-cream hues existed in the days before all cars should ideally be silver. In the same image, a 1960s concrete building, which would conventionally be perceived as ugly, surprisingly coheres with its environment as the colour of its beige vinyl window panels are repeated in the now funky VW Transporter van nearby.

Underneath each photomontage, the black and white photographs perform similar poignant tasks but use different, more restrained methods: for instance, in one, a kitsch funfair bounding tiger placard is juxtaposed with the prim ‘No Dog Walking’ sign.

In conclusion, bittersweet emotions result from the wave of nostalgia that is provoked by the collated imagery. This is the manner by which the viewer is encouraged to observe and appreciate the environment of much-maligned Rhyl. Stephen Clarke beguiles us with the quirky and forgotten scenes so that we leave the exhibition longing for what we previously denigrated.

Dr Emma Roberts.