Charlie ‘Smokey’ Phillips is an unsung hero of urban photography, and one of Britain’s most important, yet historically overlooked, photographers.

His photographs of Muhammad Ali and Jimi Hendrix sold around the world. Cartier-Bresson was a fan, while Fellini liked him so much he put him in a film. Yet in the UK, Phillip’s work was ignored for decades

Jamaican-born and raised in the ghetto that was Notting Hill, west London, in the 1950s and 1960s, Charlie is a legend in his old borough, a man known for his humour and warmth, his style and his opinions.

Charlie left Jamaica aged 11, taking the ocean steamer to join his parents in London, who were part of the Windrush generation.

Like many Windrush-era immigrants, his family did not come to Britain because they were poor but because they were invited. In Jamaica, his parents ran a business making tourist souvenirs, employing six other people. “The mother country called, so we answered,” he says. “But we never had any welcoming party; we had to fend for ourselves.”

Charlie never planned to become a photographer. His childhood dream was to be an opera singer, or a naval architect but they were not considered realistic. “They laughed at me at school. The youth employment officer said: ‘Why don’t you get a job with London Transport? That’s more security. Or join the RAF or get a job with the post office.’”

But then a camera fell into his lap.

During the late 1950s, African American servicemen stationed in the UK would seek out underground parties in West London’s illegal dance halls and basement shebeens. They would arrive with rhythm and blues vinyl and all sorts of goodies, looking for a good time. Charlie received his first camera, a Kodak Brownie, by way of one such serviceman who, desperate to return to his base after a memorable night, pawned his camera to Charlie’s dad in exchange for his taxi fare. The serviceman never returned to redeem his camera, and thus Charlie’s photography journey began.

He dove right in, bought a DIY photography manual, and taught himself to make prints and soon began amassing a thorough and intimate body of work, focusing primarily on his local community, documenting the social implications of the immigration influx, life on the streets, local musicians, African Caribbean funerals and the zeitgeist movements of that time.

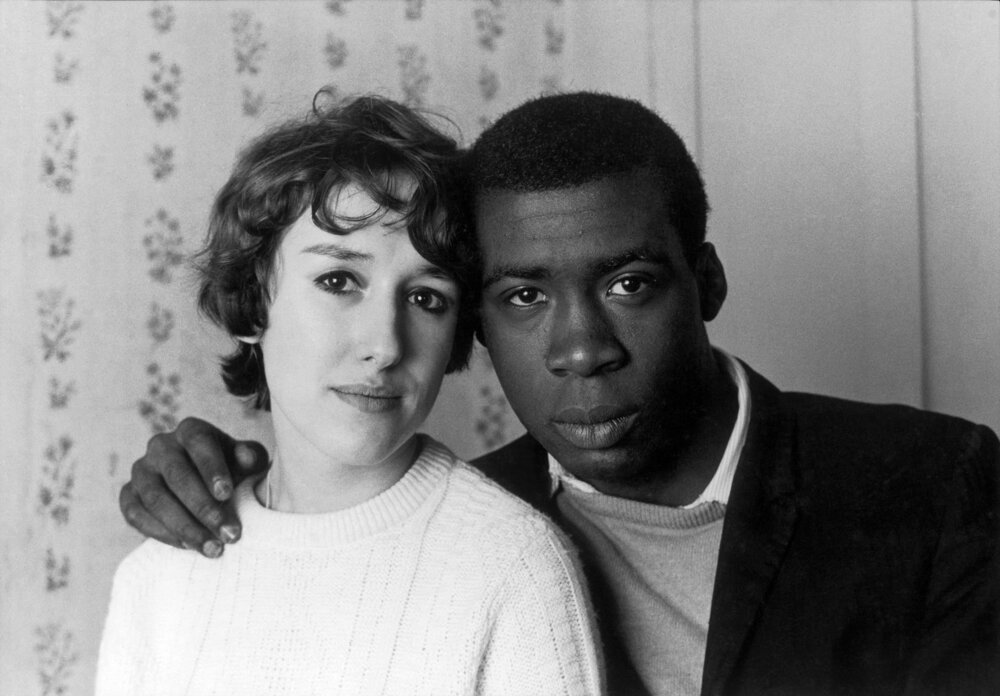

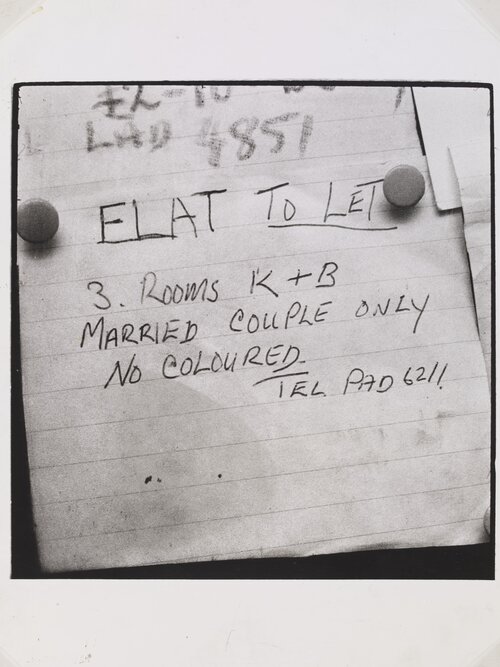

This was an era marked by regular racist assaults on the African-Caribbean community, and the 1958 Notting Hill “race riots”. Phillips’s images show hand-scrawled adverts for rooms to let, spelling out “No coloured”, and graffiti on walls reading “Keep Britain white”. But his work also captures black and white Londoners socialising together, laughing, drinking, kissing. One of his best-known photographs, known as Notting Hill Couple, has come to symbolise that spirit. Taken at a party in 1967, it depicts a young Black man with his arm around a young white woman. Both look into the camera with serious expressions that could be interpreted as hopeful, innocent, perhaps even defiant.

Charlie’s photographs have appeared in publications such as Stern, Harpers Bazaar, Life and Vogue. His work has been exhibited at galleries across the world, including the Tate Britain, the National Portrait Gallery and the Museum of the City of New York.

www.charliephillipsarchive.com